|

Do Police Use Deadly Force Too Often?

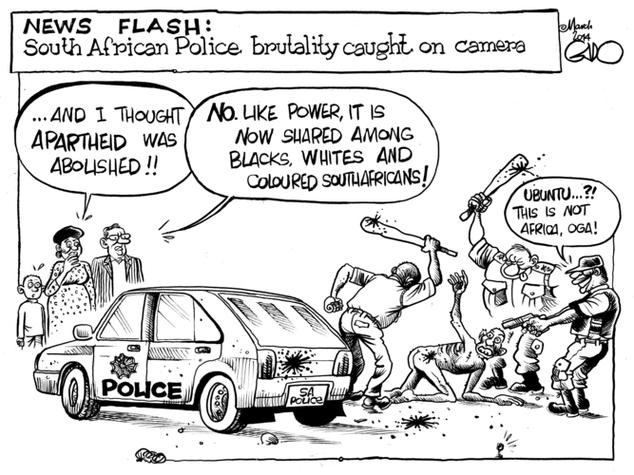

Some have called a South Carolina police officer’s fatal shooting of an unarmed black man an aberration. Others call it a too typical act of police racism. But it is undoubtedly one of a growing number of cases in which police killings of unarmed people have drawn national attention. Have police officers become too willing to use force or are they reacting to the dangers they face every day?

* fatal shooting = 치명적인 총격/ unarmed = 무기를 가지고 있지 않은/ aberration = 일탈; 일탈적인 행동(일)/ typical = 전형적인, 대표적인/ racism = 인종 차별(주의); 인종 차별 행위/ undoubtedly = 의심할 여지없이/ national attention = 국민적 관심![]() 경찰은 너무 쉽게 무력 사용을 하게 되었나요 아니면 그들이 직면하는 위험에 반응하는 것인가요?

경찰은 너무 쉽게 무력 사용을 하게 되었나요 아니면 그들이 직면하는 위험에 반응하는 것인가요?

1. Don’t Ask If a Shooting Is Justified, But If It’s Avoidable

Too many officers see themselves as warriors, vigilant against enemies, not guardians, protecting the community.

2. Deadly Force Is Rare, Scrutiny Has Risen

YouTube-inspired outrage only exacerbates the difficult task of balancing personal safety and public protection for cops who care.

3. The Public May Finally End Its Denial

The shooting made clear that some cops lie and think they can get away with murder. And the victims are disparately black.

4. No Way to Tell Without a National Database

The F.B.I. tracks justifiable homicides by police, but it only includes self-reported data from 750 agencies.

Sample Essay

No Way to Tell Without a National Database

The police shooting of Walter Scott in North Charleston, S.C. seems to many to be the latest occurrence in a disturbing pattern of police officers using deadly force against unarmed African Americans.

Are officers more likely to employ deadly force than ever before? Or is it the national focus that is new? Have the widespread use of camera phones and social media made it difficult for officials to ignore issues that have persisted in many communities for years? A central question, of course, has been whether implicit (or explicit) bias explains why officers use greater force in some circumstances.

It is impossible to determine the scope of the problem without a comprehensive national database of the number of people killed by police officers. Although some groups do track when police use serious force, a federal database would help policy makers identify not only dangerous trends and determine whether police use force disproportionately against minorities, but best practices, and thus ultimately develop policies that prevent more deaths.

While the Department of Justice collects some data on officer-involved shootings, it does not require the nation’s 17,000-plus local law enforcement agencies to all report to a central database. Instead, the F.B.I. tracks justifiable homicides by police, but it only includes self-reported data from 750 agencies. Indeed, while the F.B.I. generally estimates around 400 deaths annually, independent researchers claim the number is closer to 1,000.

In December 2014, the President signed the Death in Custody Reporting Act, a law requiring states and local law-enforcement agencies that receive federal money to make quarterly reports about the death of any person who is detained, arrested or incarcerated.

This law represented a remarkable step toward greater transparency in officer-involved fatalities, but a truly accurate database should require local police departments to report not only the deaths that occur, but any serious uses of force. More complete information regarding the circumstances under which an officer is involved in a fatality or non-fatal injury would be a valuable tool to discerning patterns of conduct, identifying areas for training or needed changes in departmental policy and increasing accountability.

|